WOODSTOCK — George Shaffer locked the door on Shaffer’s Catering, Barbecue and Deli in Woodstock for the last time on Feb. 24.

It was a sad moment not only for Shaffer, but for the thousands of people who enjoyed the familiar pimento cheese or famous barbecue — pork, chicken, or beef — and for the dozens of people who worked both part time and full time for him.

Brides and grooms, convention attendees, dignitaries, politicians, movie stars and everyday blue-collar workers looking for a chicken salad sandwich or the famous broccoli salad have enjoyed the culinary delights that were produced for decades in the Shaffer kitchen.

Since closing the door in February, Shaffer has spent countless hours packing and unpacking a business that stretched over decades, transversed thousands of miles, employed countless people of all ages, and fed millions of mouths from as near as Main Street in Woodstock to as far as West Virginia, Pennsylvania or Washington, D.C. File cabinets, invoices, receipts, personnel files, tax documents — there's a lot to go through.

“You have no idea how much stuff there is,” Shaffer said, shaking his head at the work yet to be accomplished.

Shaffer admits there is never a good time to stop working, but at 77 he no longer wanted to work seven days a week, a schedule he kept for more than 30 years.

“It’s been a good run,” he said nostalgically. “We cooked a lot of chicken. We met a lot of people ... This was such a good place to grow up.”

Eggs came first

From a lunch counter to a barbecue pit, from indoor wedding receptions to picnics on a lawn, from a deli shop to a hot-meal delivery service, Shaffer has been providing food for more than four decades.

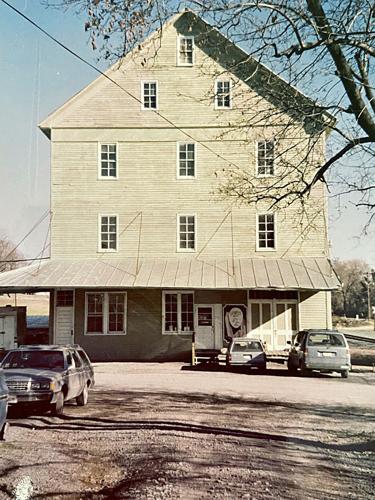

Yet it was decades prior to George Shaffer that his grandfather Vernon Shaffer laid the cornerstone of the Shaffer business, a name linked to local business for nearly 100 years. Once a shipbuilder, Vernon came to the Valley in the early 1920s and worked at the White Daisy Flour Mill when he arrived. Later, in 1923, he purchased his own mill on Maurertown Mill Road.

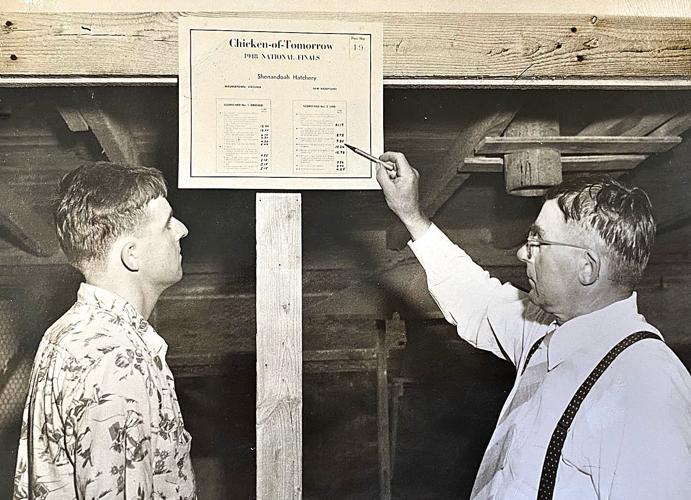

It might have been Vernon Shaffer who started the family’s unquenchable quest to diversify because soon after the mill was operational Vernon Shaffer purchased a chicken incubator with a 1,200 chick capacity, starting the Shaffer’s association with eggs and chickens: Shenandoah Commercial Hatchery.

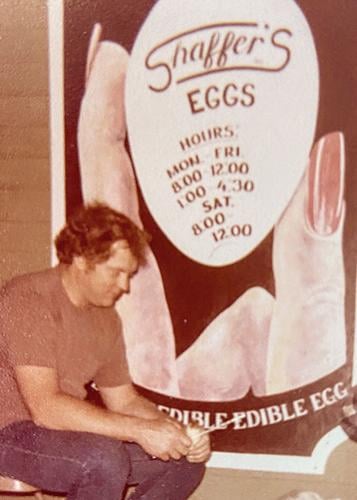

“I can remember the big incubator,” George Shaffer said, explaining the incubator was so large it was used as a closet in the former building on Locust Street in Woodstock, a historic building affectionately known as the “egg house" that was the victim of arson in August 2022.

Shaffer explained that this early Maurertown incubator — and later a two-story brooder house — produced baby chicks, chickens and eggs that were sold throughout the region. By 1935, this business was named as one of Virginia’s largest hatcheries with incubator capacity of over 110,000 eggs every 21 days and a brooding house with a capacity of over 4,000.

“We sold eggs to local grocery stores,” said George Shaffer of his grandfather’s growing business.

But the business did not stop there. There was a small orchard behind the mill, said Shaffer, explaining that the apples from that orchard were collected and sold.

This started the Maurertown Canning Company, a processing plant that by the 1940s was producing 20,000 cans per day. Nearly a century ago, “at one time, apples were barreled and shipped to England,” said Shaffer, explaining the business did not stop with apples.

The Maurertown cannery produced tomatoes, beans, pumpkins, peaches and apple juice under the label “Shenandoah Queen.”

Shaffer laughs as he remembers being a boy of 6 or 7 and helping in the cannery. “I would push the apples into the water,” he said, explaining that the conveyor belt would move the apples to the squeezing process where the juice was made. The cans came into the factory and left the factory by train car.

Matt Shaffer, George’s son, remembers the story his grandfather, John D. Shaffer, told of being in North Africa during World War II. In the mess hall, John D. Shaffer was given a can of apple juice produced in Maurertown. Turning the can over, John D. Shaffer noticed that he had been the one to mark that specific can of apple juice.

“It started as a seasonal business,” explained George Shaffer of the Shenandoah Queen label, and in 1955 the cannery was sold to Bowman Apples, currently Bowman Andros Products LLC of Mount Jackson, and later to Fillibuster’s Distillery. As a side note, George Shaffer laughs as he speculates his grandfather — a Baptist teetotaler — might not be too happy knowing his cannery is the location of a modern-day distillery.

Now Vernon Shaffer was not content just to work within the community, so in 1950 he was elected a delegate to the Virginia House of Delegates and served until his death in 1958. George Shaffer remembers going to Richmond with his grandfather, roaming the General Assembly corridors and playing in his grandfather’s office. Shaffer said sometimes his grandfather would let him “push the button” to vote.

All the while, the chicken business was growing — 600,000 strong with eggs distributed from New York to Georgia. By 1958, the egg business was so strong, that Vernon Shaffer purchased the Boyer Grocery building on Locust Street and moved the egg business to Woodstock where it was housed until 1990.

Just around that time, “Uncle Bill [Shaffer] took the chicken business to Illinois,” said George Shaffer, explaining more and more large farms were being developed in the mid-western states.

The barbecue business

But prior to that move to the midwest, brothers Bill and John D. Shaffer started the barbecue business as another seasonal arm of the Shaffer enterprise.

In the early 1950s, Woodstock hosted aqua-ramas at what is now WO Riley Park on Summit Avenue. “They were huge water shows,” said Shaffer. Feeding those larger audiences in support of the Woodstock Rotary was the Shaffer brothers' novelty dish — barbecued chicken.

“Now, you got to remember, chicken was still a Sunday dish,” laughed George, explaining barbecue chicken was not something people in the Valley had eaten before.

Bill Shaffer acquired the secret recipe from a visit to Virginia Tech, and John D. Shaffer saw the benefit.

“Dad really took off with it,” remembers George Shaffer, explaining that during the 1950s and into the 1960s, employee picnics were commonplace and well attended. Those crowds enjoyed the Shaffer barbecue chicken.

That chicken was so popular that by 1956 the Shaffer family acquired a stand at the Shenandoah County Fair and the Chicken Palace was born.

And even though John D. Shaffer kept the egg business after his father died in 1958, it was time to diversify again. John D. Shaffer partnered with Potomac Butter and Eggs and sold eggs throughout the state as well as locally.

At this same time, in addition to the store on Locust Street, John D. Shaffer along with with various friends, started a chinchilla business in addition to the egg delivery service.

“They had a chinchilla ranch,” laughed George, remembering the little rodents that were extremely popular during the 1950s and 1960s because “this was the height of fur [coats].” The chinchilla has thick velvety fur that was sought during this time period when women’s and men’s authentic fur coats were fashionable.

George explained that his father even became a certified chinchilla-coat judge, going as far as Atlanta or Minnesota to both judge and enter pelts. The pelts were sent to New York where they were graded. Those pelts not making the grade were returned to George’s father. “He did this for about 10 years,” said George Shaffer, recalling funny stories about the chinchillas and the fur — but these stories remain family stories.

All the while, John D. Shaffer’s quest for the perfect barbecue pushed the menu. George Shaffer explained that his father was always looking for another angle. John D. would visit a place in North Carolina where pork barbecue was popular. When John D. returned from his trip, he would try and try again to replicate the sauce and cooking process.

“He was never given the recipe,” said Shaffer, adding that each time his father would return to North Carolina, he would take his own Shaffer sauce, only to be told he was getting close but not quite on target.

John D. Shaffer added the pork option to the chicken barbecue in the 1970s — adding another stand at the county fair and a pavilion for diners to sit. Catering for the Texas State Society brought in the brisket, another barbecue option.

When George Shaffer returned from a stint in the United States Navy in 1974, it was his turn to diversify the business. When he joined the business in 1975, he suggested that since his father was selling eggs through Potomac Butter and Eggs they should branch out with cheese and butter at the Locust Street location.

Besides eggs, customers could choose from a variety of cheeses — cheese that arrived as large, round wheels, not in plastic packaging.

It was in 1976 that Shaffer’s Barbecue catered the large Republican event hosted by former U.S. Sen. John Warner in Atoka, Virginia. George Shaffer shook his head trying to remember the exact proposal for individualized meals, but “I really must have undercut the others” because Shaffer’s was given the contract.

“We did that for 15 years,” Shaffer said. It was nothing for George Shaffer and his crew to serve 3,000 to 3,500 hungry visitors — the chicken pits set up early with young men working hours before the food was served.

Shaffer said he remembers the largest 1978 Atoka dinner — more than 4,500 people attended when Warner was married to actress Elizabeth Taylor. Shaffer points to his cheek, explaining after the meal was served, Taylor gave him a “kiss on my cheek,” he said laughing.

Those afternoon lunches on the Warner grounds set Shaffer on the course to catering large and small events. From events at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville, to the Jefferson Memorial or the National Arboretum in Washington, D.C., and to Virginia’s southeastern shores, Shaffer carried his Chicken Palace on the road. He laughs as he remembers catering a lunch for the National Catering Society.

“Here we are catering for the world’s best caterers,” laughed Shaffer, explaining that the group was so impressed Shaffer’s could provide food for thousands without a kitchen one step away.

“We would load up the trucks and go,” he said.

But as the decade changed, the need to diversify reared its head again. In 1980, Shaffer offered to do the catering for the wedding reception of a good friend.

“She [the mother of the bride] asked how many weddings I had done” before this 1980s event. “I had to tell her — none,” laughed Shaffer.

But that wedding’s success took the barbecue story to a whole different level — local events/wedding catering.

Space, demand and diversification became the issue, so in 1990 Shaffer moved the business to South Main Street in Woodstock, the current home of Mary Bonitas, Tendia Hispana and Golden Cuts barber shop. That moved closed the egg business but gave rise to the food service from a deli counter, to catered events, to specialty platters.

Before changes were made to Woodstock’s water retention, Shaffer said “we flooded eight times in 10 years,” of the location. Moving to the final destination at the south end of Woodstock in 2000 created restaurant seating, a buffet, deli meats and cheese, and the ever-growing event catering spaces.

The facility provided more space for equipment, the opportunity to broaden deli counter sales, a kitchen to produce unique recipes, and space for diners.

Matt Shaffer remembers Patsy Hockman, who worked for Shaffer’s for more than 30 years and passed away in March. “She was the heart and soul of the place,” said Matt Shaffer, explaining “Hockman built and ran the kitchen.”

Christmas parties, corporate events, weddings, and special occasions filled the schedule until the pandemic in 2020 shut down not only Shaffer’s but the entire nation.

“We never really came back” from the pandemic, said George Shaffer, shaking his head. A man who always has a story or a joke did not have either when remembering the long days of 2020.

He said business changed after the shutdown with “companies learning to do things differently;” demands being different. “There is just not enough business to continue.”

Without the demand of the store seven days a week, Shaffer suddenly has new hours in the day.

“I think I might be getting lazy,” he teases but admits that each day is filled with demands as papers need to be sorted, files need to be addressed, and calls need to be made.

“There are no long extended trips, no vacations planned,” he said, the familiar Shaffer smile tugging at his lips. “I’m just going to get simplified.”

(0) comments

Welcome to the discussion.

Log In

We will consider two submissions per writer per month. Letters: 250 or fewer words. Commentaries: Under 500 words. You may submit a photo with a Commentary if you like. Email submissions to news@nvdaily.com.